Foreword

Louis Vyhnanek’s Unorganized Crime: New Orleans in the 1920s is an unparalleled study of New Orleans during Prohibition. While Vyhnanek’s book is the best on the subject, it lacks in certain areas. Either Vyhnanek didn’t know about, or didn’t think it was worth to mention, various gangs or individual gang leaders. And some of the individuals he does mention are incomplete.

Going straight to the sources, this writing is a trip of the New Orleans underworld from 1918 to 1932. Though the lives and careers of dozens of criminals will be covered, some will be purposely left out. Mainly the career of Jack Sheehan, which is covered at length in Unorganized Crime, will be absent. This writing is also strictly a criminal history of New Orleans, mostly in the French Quarter, during this time period. For a political/law enforcement/anthropological look at New Orleans during this time, Vyhnanek’s Unorganized Crime is the place to be.

The original purpose, which is still the overall purpose, of this post is to document how this vastly ethnic underworld eventually fell into the grip of the Mafia with the rise of Sylvester “Silver Dollar Sam” Corolla during the twilight of Prohibition, and with the consolidation of vice in New Orleans with the ascension of Carlos Marcello in 1947.

1918-1920: The Terminal Gangsters & The Holland Gang

Before the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920, the name of two notorious gangs stained the front pages of The Times Picayune: The Terminal Gangsters and the Holland Gang.

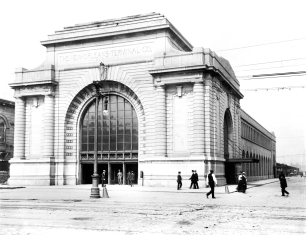

Gus Tomes, alias “Dutch Gardner“, Thomas Pepitone, Christy Burkhart, alias “Young Chancey”, Frankie Mullen, Robert Hackett, Harold “The Parole King” Normandale, Paul “Battling” Barrere, and Fred Kelly were the most notorious members of the Terminal Gangsters. Named after the Terminal Station which they defended as their turf, the majority of the gang members were livery car drivers. The gangsters would pickup their fare, and then would proceed to rob them; but the gang’s activities didn’t stop there. Robbery, illegal gambling, political intimidation, and narcotics were also extra curricular activities of Terminal Gang members. The gang’s crimes became so brazen, that on the mayoral election day of 1920, “Young Chancey” was the leader of an automobile squad that shot up the Third Ward in the interest of Mayor Martin Behrman (1).

Terrorizing New Orleans from 1918-1920, the Terminal Gang was under the protection of the NOPD and Mayor Behrman. Behrman, who had a private line to his police superintendent, was effectively in charge of the NOPD during his reign as mayor (2). It just so happens that the Terminal Gangster’s HQ was located right next to the police station, on 118 North Basin St. During the late evening hours, the gang would park their livery cars on the corner of Rabito’s, named after its owner John Rabito, and hold illegal dice and card games (3).

But the gang’s rule wouldn’t last. The defeat of Mayor Behrman in the 1920

election sealed the gang’s downfall. It would only take the new police superintendent, Guy Molony, only 60 days to decimate the gang(4). Molony’s first step was to instantly revoke all of the chauffer licenses of the Terminal Gang members(5). These licenses would allow the gang members to congregate at the Terminal Station, because when police would ask what they were doing there, they just told police that they were waiting for fares. Without their licenses, the gang members vanished from the Terminal Station. Molony also conducted raids on the gang’s hangouts, including Rabito’s. When some of the former gang members tried to relocate their hangout to Bucktown, the residents chased them out with “shotguns, sticks, and their fists.”(6)

One by one, the more prominent Terminal Gang members would either end up dead or in prison. Gus Tomes, aka “Dutch Gardner” would kill two cops in St. Bernard Parish, and would get life in prison. Thomas Pepitome was killed by Richard Kenney, not a member of the gang, but someone who would frequent Rabito’s. Kenney would be found innocent on a self defense plea. Christy Burkhart, alias “Young Chancey”, was killed by Alexander Kostakis, a Greek restaurateur in 1923. Robert Hacket was shot and killed on Tulane Ave in 1924. The rest of the gang members mentioned above would end up in prison under various charges (7). While the most notorious members of the Terminal Gang would be killed or imprisoned during the opening years of Prohibition, some of its members did graduate to smuggling liquor.

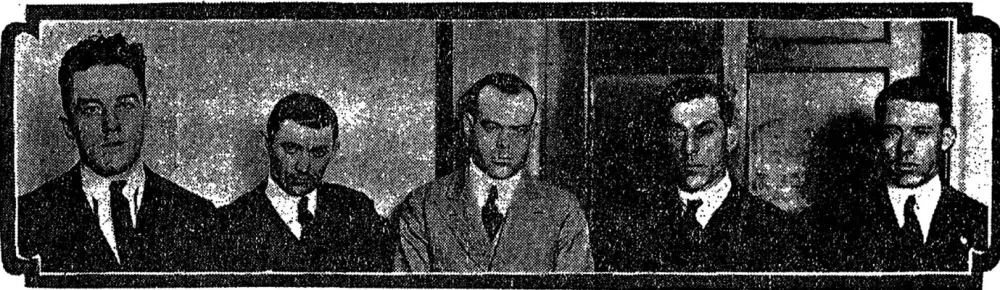

The Terminal Gang was not the only group to appear in New Orleans headlines during the early days of Prohibition. The Holland Gang was a group of stick up men and bank robbers, named after its leader Robert Holland. In September of 1921, Holland led a gang of robbers in a daring daylight robbery of the Industrial branch of Hibernia Bank and Trust, escaping with $8500 (8). Holland, and his compatriots were soon arrested, and at his trial in January 1921, it only took 12 minutes for a jury to convict him (9). Roswell Keys, Charles Ringer, and William Weston, all accomplices of Holland, were also charged in the robbery, but received separate trials. Another Holland Gang member, Edward T. Sherlock, was going to trial at the same time for the robbery of Harry’s Loan Office on Canal St. and with conspiracy to rob the American Express Co (10).

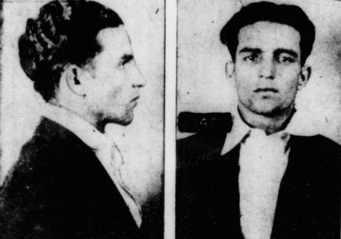

Holland Gang Members (From left to right): Roswell Keys, W.D. Weston, Edward T. Sherlock, Harry Ahearn, and Robert Holland

As mentioned earlier, some of the Terminal Gangsters graduated to rum running with the passing of Prohibition. On the early morning of Tue, November 10th, 1920, on the banks of the McDonoghville levee in Gretna, Chief Deputy Sheriff Arthur Miller, his cousin, Chief City Marshall Joseph Miller, his uncle, Deputy City Marshall Fred Millerand, and finally Joseph’s brother, William “Buck” Miller, hid in wait for a group of bootleggers to come a shore from the Mississippi River. Buck called his family of law officers earlier that night when he saw some suspected bootleggers on a skiff right next to the levee. When the criminals spotted the family of lawmen, they quickly anchored and abandoned their vessel and its contents (11).

The four men decided to stay on the levee to see if the bootleggers would return. A thick fog rolled in, giving them the perfect cover. Around 1 o clock the next morning, the four men reappeared. Returning to their anchored vessel, and presumably blinded by the fog, Peter Geanusis, former sailor and Terminal Gang member, Henry L. Herard, another former Terminal Gang member, Frank Muscurelo, known liquor runner and former Terminal Gang member, and Anthony Vaccarro walked right into where the Miller clan was waiting for them (12).

The bootleggers were so unaware of what was waiting for them, Willie Miller yelled “look out” to his brother Joseph Miller, who stepped out of the fog and came face to face with Peter Geanusis. After recognizing him from earlier, he stuck his gun right into Geanusis’ belly and told him to halt. Geanusis went for his pistol, and Joseph Miller fired his. Unfortunately for Joseph, his pistol misfired, allowing Geanusis to shoot him twice in the arm. That’s when gunfire erupted. Despite getting shot in the ankle, Geanusis proceeded to run away from Miller up the levee. Though wounded, Joseph chased him. With over 20 shots being fired, it wasn’t clear who shot who, but after losing Geanusis in the fog, Joseph returned to the site of the gunfight. There he found the dead body of Frank Muscurelo, and his cousin, Deputy Sherriff Arthur Miller, reloading his weapon. In a scene straight out of a western, while slipping more rounds into his pistol, Arthur told his cousin that he thought he was wounded. Joseph then quickly noticed a bullet wound in Arthur’s stomach. Both men were rushed to Charity Hospital (13).

After the gunfight, Geanusis and Herard hurried to Vaccarro’s automobile and were both arrested a short time later at the Canal street ferry landing, a little more than a mile and a half from the gunfight. Vaccarro was also shortly captured after, and was identified by Joseph Miller as the fourth gang member (14).

Arthur Miller was operated on immediately by surgeons, but since the bullet penetrated his intestines, there was little they could do. He would soon succumb to his wounds. Joseph’s gunshots were not serious, and was released later that morning. Probably the most tragic part of this shootout is that both Miller and Muscurelo (29) were both fathers. When Muscurelo’s widow was notified of his death, she told reporters “Oh, What will become of my children?”(15)

1920-1929: Hijacking

And with that, Prohibition started off with a bang in New Orleans. Along with it began the careers of some of the most notorious members of the New Orleans Underworld.

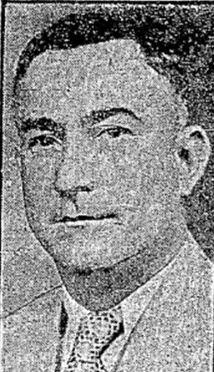

Born in 1891, William “Bill” Bailey would be approaching his 29th birthday as Prohibition would present him with a new career path. An Army deserter and an ex-cop, Bailey would become one of the leading hijackers in New Orleans (16). His partner, Manuel Acosta, born in 1871, would also choose a new career path with Prohibition and would eventually become “a figure in the legends of rum-running along the gulf coast (17).”

In 1923, already having a well established reputation as a rum runner and hijacking figure in New Orleans and St. Bernard, Acosta would narrowly escape a police raid. On the night of Wednesday, May 2, 1923, Acosta would receive a phone call telling him that he can purchase 40 cases of champagne at a discounted price. When he arrived at 2002 Prytania Street, he was greeted by four men: Jerome Clark (23), George Clark (25), Vernon Paaren (25), and Ralph Blake (24). Thankfully for Acosta, the deal fell through without violence, and he left. Moments later, detectives raided the house and took the four men into custody. But the detectives were not there for the alcohol. A week before, the Clark brothers, Paaren, and Blake robbed a saloon on Decatur street. Paaren was also identified as the man who broke into the home of a New Orleans couple at 2221 Calhoun St. and threatened them with a gun when they walked in on him.

When interrogated by police, it turns out that all four of the men came to

New Orleans from Chicago five months earlier, and committed several robberies and holdups. Though not captured during the raid, one of the bandits must have ratted on Acosta, because he was picked up by police soon after. With having nothing to hold him on, Acosta was quickly released (18).

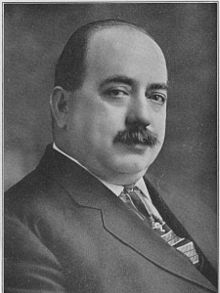

1923 would also be the year future Mafia boss Sylvester “Silver Dollar Sam” Corolla’s name would first appear in newspapers. Though his later crimes would eclipse his early career, Carolla was sentenced to two years in federal prison for stealing eighty nine drums of alcohol (19).

By 1925, Bailey and Acosta’s bootlegging and hijacking operations received more attention from the press. On the evening of Sunday, January 18, bootleggers Peter Picone (23) and Gus Toysal (24) were driving on Gentilly Road. Picone was leading in a Cadillac filled with whiskey, while Toysal followed behind in a Durant filled with whiskey. Eventually the two men came across a Nash automobile parked across the road; blockading it. As soon as they stopped their cars, two men stepped out from behind the Nash, with pistols in hand. After telling Picone and Toysal to exit their vehicles, the two men identified themselves as Prohibition agents. But the ruse didn’t last. Once Picone and Toysal exited their vehicles, they instantly recognized Bailey and Acosta as the faux agents (20).

Once they realized their cover was blown, Bailey and Acosta then informed the bootleggers that “No, we’re only nice little hi-jackers, and we’re going to take your liquor.” Bailey then got into Picone’s Cadillac and took off. Acosta got into Toysal’s Durant, but was unfamiliar with how to operate the vehicle. In a moment that had to be the most embarrassing hijackings in history, Acosta abandoned the haul to flee in his Nash. Picone and Toysal were glad to tell police who hijacked their caddy, but became suddenly silent when asked what happened to the missing alcohol in the abandoned Durant (21).

However, the stolen alcohol didn’t belong to Picone or Toysal. It belonged to husband and wife bootlegging team Arthur and Jackie Crosby. Jackie Crosby, also known in the New Orleans underworld as “Dizzy Jack” and “The Queen of Bootleggers”, made several threatening phone calls after the hijacking to Bailey’s mother. According to Ms. William J. Matthews , William Bailey and Arthur Crosby were partners. After Arthur double crossed Bailey on a business deal (Arthur told Bailey that the boat carrying alcohol to Louisiana had burnt, thus the deal was lost. In actuality, the cargo did arrive, which Arthur sold), it seems that Bailey decided to take revenge by hijacking his alcohol. Bailey’s mother also admitted to police that despite having protection from Prohibition agents and police, the Crosby’s have been having trouble safely transporting alcohol through New Orleans since the double cross (22).

A little more than two months after this incident, Bailey was now patrolling the streets of St. Bernard Parish on a motorcycle. On the evening of Sunday, April 5, 1925, Deputy Guerra set out to arrest Bailey. After seeing a man on a motorcycle parked on the side of Paris and St. Bernard road, he told him to move along. Bailey obeyed, and took off, but only to quickly pull over on the side of the road. This confirmed Deputy Guerra’s suspicions that the rider was Bailey. Guerra new the game. Bailey would act as a spotter and lay in wait for a shipment of alcohol. Once spotted, he would ride off and warn his compatriots, who would hijack the liquor (23).

Guerra then pulled over to the side of the road next to Bailey, again. Guerra informed Bailey that he was under arrest. Upon hearing the news, Bailey said “I’m just here to protect liquor”, and went for his pistol. Unfortunately, Bailey was too slow on the draw, and Guerra quickly had his gun on Bailey, who instantly surrendered. Bailey then tried to bribe Guerra with alcohol, money, and even his motorcycle. Guerra wasn’t having any of it, and hauled Bailey to jail. Bailey wasn’t in jail long before he was visited by Acosta, who was already making plans to get Bailey out on bond (24).

1929: Narcotics

New Orleans during the 1920s was named one of the largest dope distributors in the South by J.A. Manning, chief narcotics agent of the Southwest Division (25). In the summer of 1929, there was a heroin shortage in New Orleans, causing dope prices to skyrocket (26). Narcotics agents were able to determine there were three major narcotic gangs, or “rings”, operating in New Orleans, all in the French Quarter. Unlike the bootlegging gangs of New Orleans, the narcotic rings had strict territorial boundaries. The Italian gangsters stuck close to the area near Canal Street. The Spanish gangsters would peddle drugs in the French Market. The Jewish gangsters were the most successful of the bunch, catering to wealthy buyers in the Garden District, or just outright wholesaling large amounts of narcotics to neighboring states. This left a rivalry between the Italian and the Spanish narcotics rings. Authorities feared a gang war would erupt after an Italian drug dealer and dance hall owner, Angelo Pavone, double crossed a Mexican dope dealer, trying to pass chalk off as heroin. The bullet riddled body of Pavone would be found by the Doullut & Williams shipyard on the industrial canal on Tuesday, August 13, 1929 (27). Trying to avoid “murder wholesale”, like the recent St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago, authorities in New Orleans launched a massive raid against the drug gangs. One of the narcotic agents leading these raids was Clarence V.B. Moore (28).

Agent Moore was first mentioned in the paper in April of 1929, when he, and Agent H.C. Williams arrested Jack Baker, a dope ring dealer. The story made news, because it was almost a year to the day that Agent Williams arrested Baker for selling drugs. While walking near the intersection of Decatur and Dumaine streets, both Williams and Baker recognized each other among the French Quarter crowds. After a brief chase through the Quarter, Moore and Williams were able to arrest Baker (29).

On the morning of Thursday, August 22, 1929, Agent Moore and Agent Julius

Pieper were trailing two suspected morphine dealers. When the suspects car stopped on Esplanade St, near Bourbon St., Agent Pieper went on foot to get another vantage point of the suspect’s car. When the pair emerged and got into their vehicle, Agent Moore rammed his car into theirs. As he exited his vehicle to arrest the dealers, one of the suspects shot Moore point blank in the face, the bullet passing straight through his jaw. The confusion of the brief shootout allowed the two men to escape (30).

This is where most historical sources of the New Orleans underworld depart reality. Though shot in the face, Agent Moore miraculously survived. He was rushed to Charity hospital, and then eventually to Touro Infirmary. After he recovered, he soon left the state to Washington(31). Most histories of the New Orleans Mafia, like John H. Davis’ Mafia Kingfish, states that Moore died, which is incorrect.

The shooting of Moore was an embarrassment for New Orleans. The Saturday of Moore’s shooting, Police Superintendent Theodore A. Ray demanded a citywide clean up of New Orleans’ one million dollar a year illegal dope industry (32). Three separate raids on the night of Saturday, August 24, 49 men were arrested and charged with the violation of the Narcotics Act. Other raids were not as successful on clearing the streets of the city from drugs. 519 Decatur St. was raided, but only a gallon of whiskey, and four cases of beer were found. 1107 Decatur St. was also raided, but police only uncovered a gambling den and a few bottles of beer. At 123 North Peters St., again, only alcohol was found. When a soft drink stand was raided at 1108 North Rampart St., another gambling den was unearthed, its owner feeling the police while the gamblers were being arrested. Admitting that it would take more than one drive against dope dealers to get rid of New Orleans drug problems, several high profile raids would continue through the fall of 1929 (33).

While police were mounting raids throughout the city, the hunt for Moore’s shooter was also underway. Immediately, two men were arrested and charged. Identified by witnesses of the shooting, both Peter Capro (28) and Armando Omare (27) were arrested and had bonds set at $15,000.00 (34). Capro had a long history of violence and bootlegging. Omare on the other hand, was a drug addict, ex-sailor, and drifter (35). Capro was marched into Moore’s hospital room, but was not identified as the man who shot him. Three weeks after his shooting, Moore would appear in the New Orleans District Attorney’s office, signing a document saying:

“In reference to the defendants, Peter Capro and Armando Omare, who have been charged with shooting with intent to murder. I desire to state that I have seen Capro and he is not the man who shot me. The defendant Omare does not look anything like the other man who was on the scene at the time of the shooting. I cannot identify either of these men as the men who were in the automobile on Esplanade avenue and whom I arrested just prior to being shot (36).”

While Capro was released on bond, Omare remained in prison, being charged with the robbery of a store messenger a week before Agent Moore’s shooting (37).

It would be Agent Moore’s partner, Agent Pieper, who would file a Blank Complaint and identify both Sam Carolla and Frank Todaro (whose niece future New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello would marry (38)) as the two men who Moore was attempting to arrest. He also identified Carolla as the shooter. While unnamed in The Times Picayune, Agent Pieper would say that the two new suspects were figures in both the narcotics and rum running circles of New Orleans. Conveniently, both men fled New Orleans shortly after the Moore shooting. While being fugitives, grand jury indictments would be handed down for the two men. It wouldn’t be until February 21, 1930, that police would be alerted that the pair were back in the city. Both were arrested immediately, and both denied shooting Moore. Eventually, lack of evidence would allow both Carolla and Todaro to be released, being cleared of all charges of shooting Moore (39).

September 1, 1929 – December 30, 1929: New Orleans’ Little Gang War

On the night of September 1, 1930, bootleggers, hijackers, and dry informants Hayes Penton (29) and Hubert Serigent (23) were at the home of John Zechenelly, 1120 Governor Nicholls St., a prominent leader of a gang of bootleggers. While at Zechnelley’s home, Penton would later testify he saw a truck full of whiskey pull up to the curb. This truck was driven by the notorious Bill Bailey and Paul Duplessis. Once the alcohol was taken off of Bailey’s truck and switched to another vehicle, Bailey and Duplessis took off (40).

A little while later, the three bootleggers heard a knock at the door. When

Zechnelley opened it, Sylvestro “Silver Dollar Sam” Carolla stood with two of his torpedoes, Sammy“Kansas City Sam” Rubdo and Joe Mendona. They all entered Zechnelley’s house and Carolla angrily demanded Where is the stuff you got from us? (41) Carolla had a reason to be angry, a few nights earlier the home of Vincent Rizzo, 1901 Ursaline St., one of the hideouts where Carolla stashed his alcohol, was raided by hijackers, and several thousand dollars worth of liquor was stolen (42).

Both Zechnelley and Penton denied any knowledge of the hijacking of Carolla’s alcohol, and the intimidating trio left. Around midnight, both Penton and Serigent left Zechnelley’s. Since Serigent only had one arm, Penton walked to the driver’s side of their “light roadster.” Just before he got into his car, he noticed a coupe and a sedan parked along side Zechnelley’s house (43).

Penton started the car, and by the time he reached North Rampart St, in-between St. Philip and Ursuline, he realized he was being followed. Suddenly, his car was forced off the road by the coupe and sedan. Penton and Serigent quickly jumped out of their wrecked car, and were met by the men who forced their vehicle to the curb, leader amongst them being Carolla. Though it was never proven, two of the other men in the Carolla’s gang were probably “Kansas City” Sam and Joe Mendona (44).

Carolla’s “gang of gorillas” attacked Penton and Serigent, beating them with clubs and blackjacks. Penton was able to escape the beating, but while running away down North Rampart St., he was shot twice by Carolla and he fell to the pavement. Serigent was then forced into the sedan, which fled the scene of the attack. While on the outskirts of the city in Gentilly, Serigent was thrown from the car with the threat If you open your mouth, we’ll kill you to comfort him as he hit the ground. Penton also survived the attack, and was taken to Charity hospital, where he was treated for gunshot wounds, bruises, and lacerations to the head. Both Penton and Serigent identified Carolla in the beating/shooting. Carolla was arrested, but quickly posted bond (45).

On the evening of Sunday, December 29, 1929, the recovered Hayes Penton, Bill Bailey, and John Zechnelley were all again in front of Zechnelley’s home on Governor Nicholls St . The reason for the meeting was never given, but it could have had something to do with Zechnelley’s upcoming departure to Atlanta, where he was going to be serving 1-3 years for violating the Volstead Act (46).

At 10:00pm, the three parted ways. At 11:15pm, Bailey returned to Zechnelley’s home for a meeting with another bootlegger named Alfred Austin (47). While Bailey waited outside, a lone car crept up Governor Nicholls St. in the dead of night. Two accounts follow what happened next:

Bailey claims he was standing in front of Zechnelley’s home, when suddenly a car roared down the street. Bailey was then shot 14 times in the abdomen and the right arm. As Bailey fell to the ground he could make out Carolla’s face in the back seat passenger side window. As soon as he heard the shooting, Zechnelley came out of his house and rushed to Bailey’s side. Before an ambulance could reach Bailey, he told Zechnelley that it was Carolla, Rubdo, and Mendona who shot him. By the time Alfred Austin reached Zechnelley’s house, he could see Bailey’s bullet riddled body being placed in an ambulance (48) .

While on his deathbed in the hospital, police Captain James E. Cripps asked Bailey if he knew who shot him. Bailey said that “Sam Carolla and his gang” were the ones who shot him. Though he said there were 4 men in the vehicle, the only face he claimed he could make out was Carolla. Captain Cripps actually brought Rubdo and Mendona to the hospital, but Bailey couldn’t identify them. Bailey would die soon after. It’s not known if Bailey actually saw Rubdo and Mendona in the car with Carolla, or just assumed they were there because he could identify Carolla. Regardless, Carolla is the only name that Bailey would give the police (49).

A slightly different version of Bailey’s assassination would be given by John Zechnelley’s brother, Jacob, who lived at 1117 Governor Nicholls street. John claimed that he witnessed Bailey park his car outside of his brother’s house. The instant Bailey exited his automobile, another drove up. A man exited the car, fired three shots at Bailey, then jumped back into the car and sped off (50).

It’s not known what version of Bailey’s assassination occurred, but what is known is the aftermath. Carolla was immediately arrested at his 242 Frenchman St. home. He claimed no knowledge of the shooting, and said he was buying phonographs during the evening, and was at home at the time of Bailey’s assassination (51). Carolla would be held for murder, without bond, while the New Orleans District Attorney investigated Bailey’s death (52).

While no damning information against Carolla could be found in New Orleans District Attorney Eugene Stanley’s investigation of Bailey’s murder, three major pieces of information would come forward:

1.) It would be revealed that it was Bailey who gave up information to Prohibition agents that got Zechnelley arrested and sentenced for violating the Volstead Act (53). But Bailey wasn’t the only “dry agent” or “dry informant” that Zechnelley knew. Both Hayes and Serigent were both well known informants. Obviously, it wasn’t that odd for known bootleggers in New Orleans to also act as informants to Prohibition agents. This was probably both a good way to stay out of jail (though Bailey was arrested over 20 times, he was never convicted (54)), and also a sure way of getting rid of any competition.

2.) Stanley believed it was an automatic shotgun that was used to gun down Bailey (55).

3.) Probably the most historically useful bit of information to come out of the investigation is Carolla’s alleged connection to Chicago Kingpin Al Capone. Though entirely inaccurate and fantastic, there is an underworld legend that claims of a Carolla and Capone showdown. The story goes that Capone, wanting to expand his illegal liquor empire to New Orleans, took a train down from Chicago to visit the Big Easy. This fantastic yarn continues to tell that Carolla, and several officers of the NOPD, were at the train station to welcome Capone. When two of Capone’s bodyguards exited the train, the officers seized them and broker their hands. That’s when Carolla approached Capone and announced that New Orleans was his town, and suggested that Capone go back to Chicago (56).

There are three problems with this story:

a.) The most obvious being that there is absolutely no proof that Capone ever visited New Orleans. At this time, Capone was a celebrity, and photographers followed him everywhere he went. Any visit from Capone would have been noticed and reported by the press.

b.) Another problem with this story is that it assumes Carolla as the Capone figure of New Orleans, which is inaccurate. Though he executed his enemies in the style of Chicago gangsters, Carolla was never the absolute ruler of the New Orleans underworld like Capone was in Chicago during Prohibition. There was no centralized criminal ruler in New Orleans during the 1920s . The investigation proved: “Whatever idea the gang or Carolla had of establishing a monopoly in the rum business was soon dispelled (57).” It wouldn’t be until after Prohibition, with illegal gambling and narcotics, that the Mafia was able to become the dominate criminal organization in New Orleans (58). There is also zero evidence that Carolla had that much, if any, control over the New Orleans police department.

c.) While there is no proof that Capone himself visited New Orleans, gangsters from Chicago did visit New Orleans in the summer/fall of 1930. Though their connection to Capone was neither proven or contradicted, these Chicago gangsters came to New Orleans to set up a (possible) Capone connection to the local liquor market. Police knew of Carolla’s attempt to reach out to the visiting gangsters, but they were soon all arrested and placed in jail for several days. As soon as they were released, the Chicago gangsters left town. (59).” After this arrest, New Orleans detectives thought there was no reason for Capone to come to New Orleans: “Capone’s gang has no reason for importing liquor in wholesale lots through New Orleans and the Gulf territory when little difficulty is experienced in bringing it across the Canadian border (60).”

Carolla’s lawyer applied for a writ of habeas corpus to the Supreme Court, because his client was being held for a crime, with no bail, and little proof. After reviewing Carolla’s petition, Chief Justice Charles A. O’Niell and five associate justices refused Carolla’s pleas. The court suggested that Carolla should apply to the criminal district court for the help he was seeking (61).

Carolla wasn’t the only one arrested because of Bailey’s murder. Just a week after Bailey’s demise, Hayes Penton was taken into custody as a witness, when it was discovered that he was at Zechnelley’s house a little more than an hour before Bailey’s death (62).

Carolla was still in prison while his trial started for the attempted murder of Hayes Penton. During the trial, Carolla would be called “the little czar of the underworld”, “a viperous bootlegger”, “and the “worst of the Chicago styled gangsters” by lawyers (63). On January 24, 1931, Carolla was sentenced to 8 – 15 years (64). His sentence would start after he completes a three year y January 1931 (65). All charges against Carolla for the murder of Bailey would be dropped, due to lack of evidence.

1929 – 1933: The Party’s Over

After the trial, Penton would flee to the North shore, where he was “lying low to keep out of sight of the members of the Sam Carolla gang (66).” Penton feared that “he would be put on the spot by the gang (67).” While successful in lying low from the Mafia, Penton wasn’t successful in lying low from the law. On March 25, 1933, Penton was sentenced to three months in federal prison for impersonating a federal agent (68).

Penton posed as a Prohibition agent and “confiscated” 10 ½ gallons of alcohol from Frank “Red” Syler, a local Covington bootlegger. After leaving with the liquor, Penton said he would return to arrest Syler. When nobody came to arrest Syler, he became suspicious, and reported Penton to the police (69).

Penton claimed that Syler’s story was false, and he and the police in Covington fabricated the story to get him in prison. Penton claimed that the Covington police knew of him being an informant, and didn’t want to be caught taking pay offs from bootleggers like Syler, who allegedly paid the Sheriff $5.00 a week for protection (70).

While Penton would escape the violence of the French Quarter, Hulbert Serigent would not be as lucky. On Thursday, March 23, 1933, while Penton’s trial would be going on, Serigent was shot in the back of the head while sitting in his car. At first, Sheda Macagoni was arrested for Serigent’s murder, but was soon released. Authorities believed an “imported killer” was responsible for Serigent’s murder, and has probably already fled New Orleans. Serigent’s murder was never solved (71).

Manuel Acosta would also soon find himself in the hands of the law multiple times towards the end of Prohibition. In 1928, Acosta was captured by the Coast Guard with seven other men trying to smuggle 862 sacks of whiskey aboard the British auxiliary schooner M. Pulido, near the mouth of the Mississippi. While Acosta was arrested, he was not indicted with the crew of the Pulido. His testimony cleared the crew of the Pulido of all charges. Acosta admitted that he made three trips in a speed boat to a schooner to pick up alcohol, but didn’t know the name of the vessel (72).

Acosta was again arrested in December of 1930, when he was a suspect in the Bailey assassination, but he was quickly cleared of any suspicion (73).

Finally, in late February of 1931, Acosta was involved in a major bank robbery.

Acosta, Sam Ficcaro, and reported Chicago hoodlum and hijacker David Lee burst into the St. Roch branch of Whitney Bank and stole $26,000.00. While getting away, some bystanders who witnessed the robbery chased after the getaway car. Lee fired a shot, which hit August Keller, one of the pursuing bystanders in the ear (74).

After the getaway, the trio counted and divided the money at the home of John Marigny, a longtime friend of Acosta, at 3223 Conti St. Marigny, and his son, John Marigny, Jr., arrived home to the three bank robbers, with their pistols on the table, counting stacks of money and burning money bands on their wooden stove. The robbers then took $2,000.00 with them and hid the rest of the stash in Marigny’s home. When the robbers returned to count the rest of their loot, they noticed that some of their money was missing. Acosta suggested to his friend that he and his son should leave town, Ficcaro suspected Marigny of taking some of the money, and mighttake him and his son “for a ride (75).”

Marigny was jumpy, but after David Lee and two other men came looking for Marigny on the evening of Monday, March 2, he and his son reluctantly went to the police. He and his son’s testimony led to the arrest of the gang and ended the career of the legendary Manuel Acosta (76).

While Carolla spent the rest of Prohibition in jail, he would receive a pardon for the Penton shooting from Governor O.K. Allen . Though free, Carolla would find himself facing a five year sentence for another violation of the Harrison Narcotics Law in 1936. Finally, the U.S. government would determine Carolla to be an undesirable alien, and would be deported from the United States in 1947(77). In concurment with Vyhnanek’s theory in Unorganized Crime, the Mafia didn’t become the major power in the New Orleans underworld until Carlos Marcello would become boss, replacing Carolla, and was able to consolidate vice in New Orleans under the rule of one powerful, centralized criminal organization. The illegal slot machines introduced by Genovese Crime Family acting boss Frank Costello in 1936-1940, with the help of Louisiana Governor Huey Long, would provide the Mafia in New Orleans with the jolt it needed to become the dominate criminal organization (78). While Carolla himself was in jail during this time, it would be Frank Todaro and a young Carlos Marcello who would muscle in Costello’s gambling machines into French Quarter bars (79).

Sources

(1) “Ray Warns City As Thuggery Looms.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 26 Jan. 1925: Print.

(2) ibid

(3) ibid

(4) ibid

(5) “Molony Takes Up Divers‘ Badges In Fight On Gang.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 21 July 1921: Print

(6) “Bucktown Folk Force Unwanted Visitors To Flee.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 19 August 1921: Print.

(7) “Ray Warns City As Thuggery Looms.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 26 Jan. 1925: Print.

(8) “Two Break Under Strain and Confess Many Crimes…” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 12 Sept 1920: Print.

(9) “Holland is Bank Bandit, Jury Says After 12 Minutes.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 30 July 1921.

(10) ibid

(11) “Alleged Terminal Gangster Present at Pistol Battle.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 12 November 1920.

(12) ibid

(13) ibid

(14) ibid

(15) ibid

(16) “Bailey’s Mother Says “Dizzy Jack” Concocted Plot.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 25 January 1925.

(17) “Officers Avert Battle in Pitch Liquor Raid.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans]

2 Feb 1929.

(18) “Police Holding Four of Alleged Bandits’ Gang.” The Times Picayune. [New Orleans] 3 May 1923.

(19) Vyhnanek, Louis Andrew. Unorganized Crime: New Orleans in the 1920s. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, U of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998. 206-09. Print.

(20) “Hijackers Seize Whiskey; Acosta, Bailey Accused.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 19 January 1925.

(21) ibid

(22) “Bailey’s Mother Says “Dizzy Jack” Concocted Plot.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 25 January 1925.

(23) “Bailey Arrested for “Patrolling” St. Bernard Road.” The Times Picayune

[New Orleans] 6 April 1925.

(24) ibid

(25) “Drive On Drug Rings Launched to Prevent Outbreak of Gang War.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 24 August 1929.

(26) ibid

(27) “Double Cross on Dope Blamed in Gang Slaying” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 15 August 1929.

(28) “Drive On Drug Rings Launched to Prevent Outbreak of Gang War.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 24 August 1929.

(29) ibid

(30) “Pair Charged With Shooting Moore Jailed.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 22 February 1930.

(31) “Drive On Drug Rings Launched to Prevent Outbreak of Gang War.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 24 August 1929.

(32) “Police Launch Drive Against Narcotics Rings.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 25 August 1929.

(33) ibid

(34) ) “Drive On Drug Rings Launched to Prevent Outbreak of Gang War.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 24 August 1929.

(35) ibid

(36) “New Clue Found in Attack on U.S. Narcotic Agent.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 10 September 1929.

(37) ibid

(38) Davis, John H. Mafia Kingfish: Carlos Marcello and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989. 39. Print.

(39) “Pair Charged With Shooting Moore Jailed.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 22 February 1930.

(40) “Liquor Racketeer Faces One to 21 Years’ Term for Attempted Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 21 January 1931.

(41) ibid

(42) “Carolla Faces Murder Charge As Victim of Reprisal Shooting Dies.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 29 December 1930.

(43) “Liquor Racketeer Faces One to 21 Years’ Term for Attempted Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 21 January 1931.

(44) “Two Beaten, One Shot in Attack by Bootleggers.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 2 September 1930.

(45) ibid

(46) “Corollo Faces Murder Charge as Victim of Reprisal Shooting Dies.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 29 December 1930.

(47) “Officers Assert Solution of Gang Slaying is Near.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans} 31 December 1930.

(48) “Corollo Faces Murder Charge as Victim of Reprisal Shooting Dies.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 29 December 1930.

(49) ibid

(50) ibid

(51) “Officers Assert Solution of Gang Slaying is Near.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans} 31 December 1930.

(52) “Stanley to Call Grand Jury Quiz in Bailey Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 30 December 1930.

(53) ibid

(54) “Officers Assert Solution of Gang Slaying is Near.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans} 31 December 1930.

(55) “Stanley to Call Grand Jury Quiz in Bailey Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 30 December 1930.

(56) Vyhnanek, Louis Andrew. Unorganized Crime: New Orleans in the 1920s. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, U of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998. 206-09. Print.

(57) “Stanley to Call Grand Jury Quiz in Bailey Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 30 December 1930.

(58) ibid

(59) “Stanley to Call Grand Jury Quiz in Bailey Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 30 December 1930.

(60) ibid

(61) “Witnessed Placed Under $2500 Bond in Murder Case.” The Times Picayune

[New Orleans] 3 January 1931.

(62) ibid

(63) “Liquor Racketeer Faces One to 21 Year Term for Attempt to Murder.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 21 January 1931

(64) “Carollo is Given 8 to 15 – Year Term in Shooting Case.” The Times Picayune

[New Orleans] 24 January 1931.

(65) ibid

(66) “Informer Jailed as Impersonator and Hijacker.” The Times Picayune

[New Orleans] 25 March 1933.

(67) ibid

(68) “Informer, Guilty of Impersonating “Dry”, Given Term.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 11 May 1933.

(69) “Informer Jailed as Impersonator and Hijacker.” The Times Picayune

[New Orleans] 25 March 1933.

(70) ibid

(71) ibid

(72) “Seven Acquitted in Plot to Bring Liquor into U.S.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 14 June 1929.

(73) “Search for $26,000 St. Roch Bank Raid Booty Continues.” The Times Picayune [New Orleans] 4 March 1931.

(74) ibid

(75) ibid

(76) ibid

(77) Vyhnanek, Louis Andrew. Unorganized Crime: New Orleans in the 1920s. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, U of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998. 206-09. Print.

(78) United States. Congress. Senate. Second Interim Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce: Pursuant to S. Res. 202 (81st Congress). By Estes Kefauver. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1951. Print.

(79) Davis, John H. Mafia Kingfish: Carlos Marcello and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989. 44-49. Print.

Caption Sources

Terminal Station

“Crescent City Choo Choo Page 1.” Crescent City Choo Choo Page 2. New Orleans Public Library, n.d. Web. 08 Aug. 2016.

Aside from the pictures of Al Capone and Frank Costello (which can be found in almost any publication about those two figures), every other picture used in this post comes from The Times Picayune.

Dexter,

That was a great and interesting story above. I knew that Carlos Marcello was instrumental in bringing organized crime to Louisiana, but wasn’t sure how it began. He was so young when he started smuggling in illegal slots for the Costello family. Very interesting. Keep up the good work, your posts are so very interesting and you are such a wonderful writer.

Thanks so much for the great story.

Carleen B. Babin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really fascinating series, thanks for posting all this!

LikeLike